The DIRE STRAITS megagame was held on September 5 at King’s College London, and formed part of three days of activities, panel discussions, and break-out sessions at the Connections UK professional wargaming conference. You’ll find my overall report on the conference here, and a BBC report on the game here.

In this blog post I thought I would reflect a little on the exercise: the rationale and objectives for the game, the scenario, game design choices, how it all went on the day, and what (if any) substantive policy lessons we can draw from it.

Game Objectives

Connections UK first held a megagame as part of the conference programme in 2016, when Jim ran War in Binni—a civil war scenario set in a fictional country. It proved very popular with participants, who expressed a desire that the conference organizers do something similar for 2017.

However, since Connections is about improving the art and science of wargaming, and most of the participants are folks who participate in, design, or facilitate professional wargames (or other serious games), we thought that this time we might try to simulate a real, near-future situation. This is a more difficult challenge: the game designer needs to accurately reflect reality, and cannot play around with that reality solely to create more interesting game dynamics.

Complicating all this were the practical requirements of the event:

- There would be more than 100 participants, and so the game had to accommodate this many roles and sub-roles. Everyone needed to be engaged and involved.

- Related to this, we wanted people to enjoy themselves. Quite apart from whatever insight the game might offer into wargaming and its subject matter, it also served as a conference ice-breaker and networking opportunity.

- Participants would have a wide range of subject matter expertise and wargaming experience.

- The game would take up much of the first day, involving around 6 hours of game play (including briefing and lunch).

- Physical space was rather limited: one large room, and two smaller rooms.

- There would be no time for pre-reading. The game briefings had to be sufficiently straight-forward to enable everyone to assume their roles with minimal preparation.

As if that wasn’t enough, we later decided to raise the bar a bit higher still by adding an experimental research component to the game. This would examine issues of convergence and divergence in wargame analysis. Specifically, would three different groups of analysts, each observing the same game and with access to similar materials and documentation, reach similar conclusions about the validity of the wargame methodology adopted and the substantive findings of the game? The megagame would give us an opportunity to explore this important question.

Scenario

Our very first thought was to do a China-Taiwan crisis, which gave rise to the title DIRE STRAITS. However, it soon became apparent that this would not easily sustain 100+ participants. Consequently, we expanded it to include other potential regional crises: North Korea’s development of ballistic missiles and nuclear weapons; China’s maritime claims in the South China Sea; and growing tensions between India and China. Virtually all of these issues were in the news, and indeed were increasingly so as the summer progressed.

At the same time as we were developing the scenario, we also settled on a central question that the game would address: how would the unpredictability of US policy under the Trump Administration, and the growing strategic power of China, affect crisis stability in East and Southeast Asia? In order to make any such effects clearer, we set the game in early 2020. The Trump Administration was said to have survived the Special Counsel investigation, but suffered political damage. Parts of the Republican Party were in open revolt, and Trump faced a Republican challenger for the 2020 presidential nomination. North Korea was on the verge of resuming major weapons tests, and suffered from growing internal unrest. In Taiwan, revelations of Chinese (PRC) efforts to hack the island’s January 2020 elections had spurred a strong pro-independence backlash there. Just to push things along, we also planned an assassination attempt against North Korean leader Kim Jong-un for Turn 2 of the game.

Marc Lanteigne (Centre for Defence and Security Studies, Massey University)., who specializes in Chinese and East Asia security issues, was kind enough to review our scenario ideas and confirm it all seemed plausible.

Game Design

Although he might disagree and break into post-traumatic twitches at the mere mention of DIRE STRAITS, it was (as in the past) a sheer joy to be working with Jim on this project. We quickly divided the work between us. I handled the scenario development and team/player briefings, the White House and North Korea subgames, and the “Connections Global News” media unit. He developed the overall game system for the deployment and use of military units, the maps, and most other game components.

We took pity on the Royal Navy and let them have the F-35Bs operational on HMS Queen Elizabeth a few months early

In developing the game system we very much emphasized relatively simple rules, with a very general combat model. With one week turns, large aggregate forces, and large areas of the region depicted, there was little need to model individual platforms and weapons system. Moreover, given that we were dealing with a series of crises that might involve more signalling than actual use of force, we decided to stress posture (how prepared and mobilized military forces were) and commitment (willingness to use force in a confrontation).

The maps used a simple system of zonal movement. Again, with one week turns, fine detail was unnecessary.

Teams were typically subdivided into a national leader, a foreign minister, a senior military commander, an intelligence chief, and one or more ambassadors. Each team would issue military orders (movement of forces, as well as changes in posture and commitment) using a Military Operations Form. Other major decisions (including options presented in the team briefing) were recorded using a Major Decision Form. In order to provide greater insight into goals and perspectives, we also had each national leader complete a Strategic Assessment each turn, while each intelligence chief completed an Intelligence Assessment to identify threats and likely future developments.

The White House subgame was an essential part of the design. In particular, we needed to recreate the uncertainties and internal power struggles of the Trump Administration. We decided early on not to have a participant playing the President himself, for fear that excessively crazy (or reasonable) behaviour might adversely affect the entire game. Instead, potential presidential policy directions were represented by various Tweets, most of them based on previous statements.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Members of cabinet and the White House staff each had different policy preferences (anti-globalism, defeating the Republican challenger, confronting China, encouraging diplomacy, projecting American military strength, promoting the Trump brand, achieving a well-run White House, or “Making America Great Again”), and sought to influence the policy by moving various ideas up a snakes-and-ladders -type game board using White House Politics cards. Some of the latter are displayed below.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

White House players who had their favoured policies adopted by the President received Trump points. Amassing these was essential, for periodic staff shake-ups could result in the ouster of the lowest-scoring player. Once a policy was in place in a given issue area, it remained there until replaced. Of course, just as in the real world, US players would have considerable latitude in how to interpret President Trump’s statements.

The North Korea subgame took a very different approach: we didn’t really establish much of a game at all, and asked North Korea Control (Tom Mouat) to improvise if need be. At the DPRK table we placed various displays indicating the various key power centres of the regime, onto which the players placed pawns indicating their loyal cadres. Not surprisingly, the Supreme Leader had the most cadres, and controlled the key positions. However, in the event that the assassination attempt succeeded, we envisaged using matrix-game adjudication to determine the success and outcome of any internal actions. Party Politics cards added some additional richness to this.

Some of the North Korean Party Politics cards.

It was important that lesser players retain support in the Central Committee lest they be purged. Kim Jong-un was also given—partly for fun, but also to simulate the demonstrative displays of public support that sustain authoritarian regimes by projecting omnipotence—a number of Obsequious Loyalty Forms. With these he could set his minions a task each turn, with rewards and punishments for those who exhibited impressive or disappointing revolutionary enthusiasm.

One of the North Korea power structures displays, in this case depicting the Korean Workers’ Party. The others depicted the military, the intelligence and security services, and the civil government.

The presence of a complex-looking internal politics game on the North Korean table was also intended to generate a sense of uncertainty and confusion among other teams as to what exactly was going on in Pyongyang.

The US and North Korea subgames might seem a little satirical, and indeed were designed to allow the players to enjoy themselves. However, we were fairly confident that their actual outputs would be quite realistic. Statements from the US President would be rhetorical and unpredictable, reflecting his own views and the intense ideological, political, and personality battles within the White House. Indeed, most were simply restatements or tweak of previous statements made by Donald Trump during the election campaign or since assuming office. North Korean politics would be complex, but opaque to outsiders. This was also a case of designing for our audience, who we knew could appreciate the humour while remaining focused on their simulated tasks.

With regard to our media team (Connections Global News), this Jim and I recruited outside the conference from among experienced megagame players and some of my former political science students (all of whom were veterans of my own intense, week-long Brynania simulation). The media play an absolutely essential role in such games, making sure that players are well-informed by providing a stream of generally reliable information. Jim was able to staff the various Control positions from among experienced gamers attending the conference.

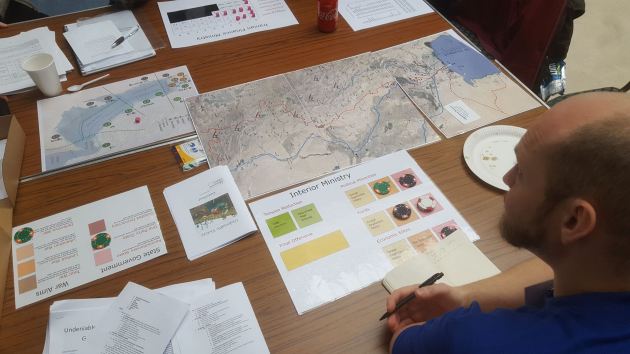

More game materials. Photo credit: Jim Wallman.

When assigning players to teams, we did our best to match subject matter expertise and experience to roles. We were fortunate to have several people with expertise in the East and Southeast Asian security issues among the conference participants.

Game Play

Both Jim and I were very pleased with how it all went. The players remained extremely active and engaged. Team behaviours were all plausible. The Control members did an excellent job, and Connections Global News managed to tweet no fewer than 365 news reports in five hours of play, at a rate of more than one per minute.

The initial CGN game briefing underway. Photo credit: Tom Mouat.

The North Korean crisis attracted the most international attention. Kim Jong-un, who survived the assassination attempt thanks to his loyal secret police, approved testing of a multiple warhead version of his ICBM, and then deployed a basic SLBM system on modified conventional submarines. The missile tests took place over Japan, moreover. Each of his decisions was met with rapturous applause from members of his government (although one overly ambitious ambassador did have to be disciplined).

South Korea, Japan, and the US responded by placing forces on alert. South Korea decided to undertake covert efforts to promote peaceful change in the North. While the DPRK’s Supreme Leader (ably played by Brian Train) projected the revolutionary self-confidence one might expect of the vanguard leadership of the Korean Workers’ Party, I think that as they saw the build-up of military hardware in their neighbourhood they might have been a little anxious as to whether they had overstepped a little.

Players react as CGN reports on a North Korean missile test. Photo credit: Tom Mouat.

Unknown to most (except the CIA), South Korea also began secret preparatory work to enable it to launch an accelerated nuclear weapons development programme at some future point, if the need arose. The growing strategic threat from the North was the primary reason for this. However, Seoul was also concerned that US commitments were perhaps less reliable than in the past. This was a concern for Japan too.

Things heat up around the Korean Peninsula. Photo credit: Tom Mouat.

Indeed, within the US Administration there was a lively, and often confused, debate over how to respond. Some felt it was essential to send a strong message of US resolve, and indeed at one point US Pacific Command recommended that the US consider sinking a North Korean SSB to send a message. That was quickly ruled out by the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Secretary of Defense. Others argued for caution, arguing if too much pressure was placed on Pyongyang the regime might respond in dangerous ways.

The White House. Photo credit: Connections UK.

When Pyongyang briefly hacked Donald Trump’s Twitter account, however, the President was furious. The NSA and US Cyber Command responded by briefly shutting down North Korean radio and television.

Inside the White House. Photo credit: Ivan Seifert/KCL.

A key point of difference within the American Administration concerned the role of China. Some favoured diplomatic outreach to Beijing to coordinate policy regarding the Korea crisis. Others felt China’s interests were too different from those of the US. Still others, with an eye on US domestic politics, were eager to advance the President’s trade policy by putting pressure on “#cheatingChina” to make economic concessions. The result was that US policy signals were mixed at best, reflecting as much the tug-of-war within the White House as the evolving strategic crisis on the Korean Peninsula. Meanwhile, the situation grew increasingly fraught, and a subsequent review of national intelligence estimates showed that several countries assessed the probability of war in coming weeks at greater than 50/50.

Everyone on alert. Photo credit: Paul Howarth.

US diplomats in their region, however, did their best to pursue a steady course, downplaying some of the President Trump’s more provocative statements and working with regional actors. China, Russia, and the US met to resolve the crisis, while both North and South Korea took steps to de-escalate the situation. The US also took the decision to expand and accelerate deployment of a range of ant-ballistic missile (ABM) systems (THAAD, Aegis, and GBD/GBI) to offset North Korea’s growing capabilities.

Game play underway at CGN headlines are displayed on the room monitors. Photo credit: Paul Howarth.

While all this was going on, the Taiwanese team—angered by the “Chrysanthemum Conspiracy” election hacking scandal—pushed for greater Taiwanese independence from the People’s Republic of China. When efforts to win observer status at the United Nations were blocked by China in the Security Council, efforts shifted to the General Assembly. At the same time, a constitutional reform process was announced, with considerable public support. Taipei hoped that Beijing would be too distracted by the Korea crisis to respond forcefully to these moves. France was particularly outspoken in supporting Taipei’s efforts, including a promise of arms sales.

Tensions grow in the Taiwan Strait. Photo credit: Paul Howarth.

The PRC’s response was rather less severe than one might have expected, Nonetheless, it did begin a build-up of naval forces in the Taiwan Strait, and sent a warning shot in the form of a massive cyberattack that disrupted internet traffic across the island. The US dispatched a carrier task force to the area, and President Trump at one point tweeted apparent support for Taiwan’s UN bid. However, back in Washington another heated debate was underway. Some favoured supporting democratic Taiwan. Other advocated abandoning President Tsai to win greater support from Beijing on the Korea issue. In the UN, the US refrained from actively supporting Taiwanese efforts.

In the South China Sea, ASEAN countries found common ground in resisting Chinese maritime claims. Such enhanced regional cooperation seemed to be spurred on by a feeling that American support would be uneven going forward. France and the UK joined several regional countries (Malaysia, Vietnam, Philippines) in naval exercises, while Indonesia announced that it would be upgrading military facilities and constructing an airbase in the area. Several countries announced more active measures against Chinese fishing in disputed waters, resulting in a couple of incidents between fishing vessels and coast guards.

Vietnam—adjacent to China, still smarting from China’s 2017 threats against an offshore oil project, and with bitter memories of the 1979 war between the two countries, was especially active in reaching out to other partners. It signed a secret agreement with the US to establish a joint signals intelligence facility to monitor Chinese military communications, concluded an arms deal with Russia, and allowed a Russian naval visit in conjunction with planned joint oil exploration in the area. Beijing was none too pleased by all this, but was preoccupied by other events.

The Vietnamese team issues new military orders. Photo credit: Ivan Seifert/KCL.

Amid all this, border tensions between India and China were quickly resolved. Although military forces were briefly placed on somewhat higher alert, the two countries quickly agreed to accept the status quo and reduce tensions. Thereafter India largely focused on economic development and pursuing amicable relations with its neighbours—except Pakistan, where tensions over Kashmir flared.

And so it was that DIRE STRAITS ended with a few incidents at sea over illegal fishing and a some major cyber-attacks, but no open warfare. This, I think, was a very plausible outcome—although the Chinese response to signs of greater independence by Taiwan were rather less forceful than I imagine their real-world response would be. While it all might seem surprisingly peaceful in retrospect, many countries spent much of the game expecting war to erupt at any minute.

We also saw the President’s beleaguered Chief of Staff dismissed from his post amidst White House intrigue, and his overwhelmed Secretary of State resign at the end of the game rather than be fired.

Broader Lessons

After all of that, what conclusions might be drawn from the game concerning both the topic under examination, and the use of megagames as a serious gaming method?

Despite the various requirements imposed by the conference and venue, I do think the game generated some insight into current policy challenges. Specifically:

- US policy under the Trump Administration is much less predictable than under any other president in modern times, a function of both the President’s mercurial and populist political instincts, and the clash between differing priorities and world-views within the White House. True, we had designed the game system to encourage this, but none of it was predetermined, and players could have taken a more cooperative route (as they did when deciding to increase the American investment in ABM systems). As White House Control, I was pleased to see how realistically and enthusiastically participants role-played their roles. Debate centred around different political views and goals, and not the manipulation of game mechanics. Domestic political concerns often trumped geopolitics. In short, if one builds a game system that models the existence of factions, rivalries, and differences within the current White House, one gets game outputs that look very much like current US foreign policy.

- The mixed and sometimes wildly oscillating signals coming out of Washington do less damage than might be the case because they are quietly spun, nuanced, and moderated by cabinet officials and ambassadors in the field. In DIRE STRAITS the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Secretary of State, and various ambassadors played a key role in this. Indeed, it was precisely because he spent so much time trying to patch over problems arising in Washington that our simulated Secretary of State found himself with little influence in the Oval Office and was ultimately sacked.

- Despite this, uncertainties in US policy generate anxiety among American friends and allies. Neither South Korea nor Japan seemed to feel they could fully rely on Washington, as evidenced by the former secret decision to prepare a potential nuclear weapons programme. Taiwan was never quite sure how much latitude and US support it had, and Beijing was also left guessing about American commitment to the “One China Policy.” ASEAN countries increased regional security cooperation in part because US backing seemed uncertain. Several countries diversified their relations to counterbalance China and hedge their bets regarding American support.

- The game clearly showed that there are no good policy options regarding North Korea’s nuclear capacity, only less-bad ones. Everyone was wary of pushing Pyongyang too far. Toppling the Kim Jong-un regime was seen by most (but not all) as dangerous, since it risked retaliation or chaos in a nuclear-armed state. In this sense, Pyongyang’s nukes demonstrated their value as a deterrent. Rather than punitive strikes or intervention, a messy mix of threats, deterrence, sanctions, and diplomatic dialogue appeared to offer the best path to crisis management. US-Chinese cooperation was important, but undermined by mutual suspicion, as well as tensions between Washington and Beijing on other issues (such as trade or the South China Sea). Overall, the game seemed to suggest no meaningful path to denuclearization, a real risk that South Korea (or even Japan) might consider a future nuclear weapons option, and the reality of having to live with a nuclear-armed DPRK while mitigating the threat and deterring North Korean adventurism.

Some of the media team (and me). Photo credit: Patrick Brobbey.

Regarding the game method, there’s not much I would change. There were a few cases where misleading information circulated (CGN initially reported Taiwan was successful in its bid for UNGA observer status, and had to correct this—no such vote was held, and they would have likely lost), but overall the information flow and quality was excellent. The subgames worked well, and it was noteworthy than many/most non-American players were unaware that “Donald Trump” was a game system rather than a human player until after it was all over. Jim’s decision to dramatically simplify the military/combat system, and to emphasize issues of posture and commitment, was absolutely right. The map displays had just the right amount of simplicity and detail.

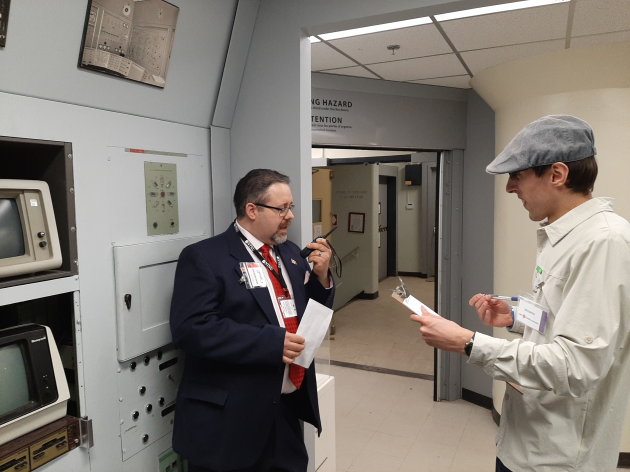

The US analytical team. Photo credit: Connections UK.

Longer turns would have been nice—I think we would have had better briefing back to leaderships as well as more considered strategy discussions. However, longer turns would have also meant fewer turns, and we thought it important that there be ample opportunity for players to see the consequence of their actions. We also surprised players by ending the game one turn early to prevent “last turn madness.”

More analysts analyzing. Photo credit: Tom Mouat.

We could have had more effective data collection, but here we were limited by the realities of the exercise. Teams did complete our military and major decision forms as required, but strategic and intelligence assessment forms were sometimes forgotten (or lost) in the hustle and bustle. All the news reports were archived, and pictures were taken of each game map each turn to provide a record of the military situation. Members of the three analytical teams freely circulated around the game during play, and were able to listen in on strategy discussions, negotiations, and sundry plotting. I’m eager to see what they will have to say.

* * *

At the moment, it looks like we will be designing another megagame for Connections 2018 (pending the results of the participant feed-back forms). The subject matter, however, has yet to be determined. Ideas, anyone?

Intervention! is a game of fictional great power intervention in the modern era, designed for 17-28 players (with a control team of four). It is playable in 2-4 hours.

Intervention! is a game of fictional great power intervention in the modern era, designed for 17-28 players (with a control team of four). It is playable in 2-4 hours.

Divided Land is a megagame set in Palestine during 1947, the turbulent last year of the British Mandate, just before the involvement of the United Nations, and the subsequent declaration of the State of Israel and the ensuing conflicts. The game has been played in Sweden and in the UK.

Divided Land is a megagame set in Palestine during 1947, the turbulent last year of the British Mandate, just before the involvement of the United Nations, and the subsequent declaration of the State of Israel and the ensuing conflicts. The game has been played in Sweden and in the UK.

Producing action cards for the more conventional forces was relatively easy but I had to consider actions for the irregular and terrorist teams involved. On the Jewish side this meant the underground paramilitary forces of the Haganah and Palmach, as well asthe terroristIrgun. (I had decided not to play Lehifor reasons I discuss later). On the Arab side it meant the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem and his so called Arab Army of Salvation. In the end I gave them Action Cards that reflected their differing philosophies and historical actions. For example, the Haganah could mount a Sabotage action or a reprisal Raid on an Arab village but would not act against any civilian targets. Irgun on the other hand could take any of the following actions:

Producing action cards for the more conventional forces was relatively easy but I had to consider actions for the irregular and terrorist teams involved. On the Jewish side this meant the underground paramilitary forces of the Haganah and Palmach, as well asthe terroristIrgun. (I had decided not to play Lehifor reasons I discuss later). On the Arab side it meant the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem and his so called Arab Army of Salvation. In the end I gave them Action Cards that reflected their differing philosophies and historical actions. For example, the Haganah could mount a Sabotage action or a reprisal Raid on an Arab village but would not act against any civilian targets. Irgun on the other hand could take any of the following actions: