The following article was written for PAXsims by Paul Strong, Stuart Vagg, Richard Perkins, and Major Tom Mouat. It is published under public release identifier DSTL/PUB108778.

Since the release of MaGCK (including the Matrix Game Construction Kit and associated resources), it has been used to support a range of analytical games at the UK’s Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (Dstl) and the Defence Academy of the United Kingdom, including the evaluation of strategic scenarios, tactical vignettes, and projects looking at thematic challenges.

The strength of the MaGCK resource pack pack lies in the discussions created by the matrix game process. Unlike other approaches, disagreements during MaGCK games often unlock deeper insights and usually facilitate the overall narrative. On numerous occasions, we found that the process highlighted potential emergent trends far earlier than we would expect when using more conventional approaches. The process is also highly flexible and the associated materials can easily be adapted to fit a wide range of scenarios and challenges. A major selling point was that it only required limited time, resources, and space to design and set up a series of games. In all of the studies where the process was utilised, we have found that the narrative-based exploratory gameplay that MaGCK enables can be used to highlight the sort of contextualised evidence that is sometimes difficult to obtain in a conventional structured wargame or a purely discussion-based event.

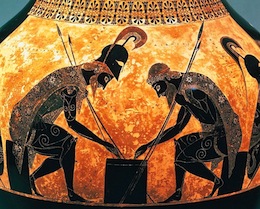

MaGCK in use at an earlier matrix game design session at Dstl.

Players in a matrix game make decisions as if they are in the roles specified in the scenario. This variant of ‘role-playing’ creates context-relevant dynamic interactions between both allies and adversaries and can be used to explore the wider implications of player decisions. The process rewards players who frame and articulate both arguments and counter-arguments to achieve their objectives (a combination of their proposed action and the intended result) in the context of the role they are playing. These arguments are then used as the basis for an adjudication process based upon the quality of the claims made by the players that contributed to the discussion. The process is a very effective approach for exploring human factors in political and strategic decision-making.

Matrix gaming tactical challenges.

The basic matrix game process in a two faction game (each faction including several players) would be as follows: The Overall Mission Narrative sets the conditions for each Narrative Challenge. The Blue player outlines their Intent – i.e. how they will overcome or exploit the situation (outlining the general arguments that support their intent) and the Effect they hope to create. This is considered by the adjudicator and, if not countered by Red, may be approved without further consideration. If the adjudicator believes that these arguments need to be explored further (or Red claims they can be countered) the Matrix approach is used. If this occurs, the Blue Player sets out a number of concise Arguments that show that their approach will achieve the objectives set out in their intent. Red then sets out a number of counter-arguments (both using their own capabilities and by highlighting real-world problems that might emerge) that provide reasons why Blue’s intent will fail. All other attendees are also encouraged to suggest either positive or negative factors, and to note any contextual issues that may influence the outcome.

Blue is then allowed to suggest appropriate mitigations that might counter Red’s arguments. The adjudicator then considers and scores the arguments of both sides – either deciding an outcome immediately or rolling dice (with a bonus for the team that presented a superior argument) to derive a stochastic result. These assumptions are recorded and the narrative continues with the new situation establishing the starting conditions. Once the adjudication is complete, the next challenge in the narrative is described and the wargame continues (the challenges do not alternate between the players – the narrative may require one side to address a series of issues before initiative is passed to the other team).

A multi-faction game (as used in political scenarios) would follow a similar process but the player actions would go ‘around the table’ in a set order (as required by the scenario context).

Unlike a general seminar discussion, both the arguments presented in the earliest turns and the outcomes decided by the adjudicator can and will be exploited by adversaries! The key to the success of the process is the adversarial interaction between the players within the framework of an evolving narrative.

In contrast to a conventional structured wargame (such as “free” kriegsspiel), where there are tables defining probable outcomes for each encounter, the players provide the tactical and technical detail that enables adjudication to proceed. This is a vital factor when the purpose of the game is to elicit insight into a force structure or challenge.

For example:

BLUE INTENT: I will order Police Unit A to occupy the bridge

EFFECT OF INTENDED ACTION: A check point will be established that will block movement across the bridge.

BLUE ARGUMENTS (pros):

- Police are nearby.

- A checkpoint can easily be established and the bridge blocked with vehicles if necessary.

- (etc.)

RED ARGUMENTS (cons):

- Police unit A is known to be corrupt (smuggling will thrive).

- The police are unlikely to stand firm if attacked and the vehicles could be removed in minutes

- (etc.)

BLUE MITIGATIONS:

- Mentoring team attached to Police Unit A

- (etc.)

ADJUDICATION:

- Where the arguments (in the context of the scenario) clearly favour one faction, the adjudicator can opt to allow the narrative to continue.

- Where there is no clear winner or the advantage is marginal, dice can be rolled to decide the outcome.

Examples of analytical Matrix games at Dstl

Future force concepts

Dstl were asked to evaluate a potential future force concept intended for consideration by the UK military (the Royal Marines Lead Commando Group). The concept used a combination of emerging technologies to facilitate an innovative approach to warfighting across a range of scenarios.

While many force evaluation exercises have tended to select from a menu of technologies and then try to understand how they might be used at the broad scenario level, the approach used for the Lead Commando Group (LCG) tested the current force and an agreed future force against a series of illustrative tactical vignettes (each set within an approved scenario). The narrative of each vignette was designed to stress each force and highlight a series of plausible ‘left and right of arc’ challenges that the LCG might have to overcome. Some were based upon the current threat while others looked at how potential adversaries might exploit similar technologies and systems. These Matrix games were run with the intention of fully investigating the potential strengths and weaknesses of each force, as well as establishing a finalised Scheme of Manoeuvre for subsequent combat modelling. This would then allow Dstl to identify insights on which of the future concept’s key capabilities could and should be integrated into the current force.

The narrative only covered the general background and wider operational objectives of the Blue force and their adversaries (conventional and irregular). This enabled the decisions of both Red and Blue to influence the evolving narrative. The pro-argument / counter-argument / adjudication approach enabled the concept to continuously evolve as it faced new challenges. Thus strengthening the concept and identifying areas where more detailed analysis might need to be conducted.

The matrix game approach proved to be a powerful tool for exploring capability. The argument/counter-argument approach rapidly identified issues and opportunities that could be explored by more detailed simulations and the discussion enabled the players to review a number of specific requirements and capabilities that might need to be adapted or developed. We found that two Blue and two Red players, with 2 or 3 neutral (but appropriately qualified) observers, was about the right mix with both sides using the discussion to develop their ideas and consider the wider implications of their chosen force design. The only negative remark about the process is that the players always wanted more time for discussion!

Security case study

Dstl were also asked to review a security-based case study. We were asked to look at the planning challenges for an adversary intending to attack a known strategic target so that an appropriately detailed and plausible narrative could be run through more detailed simulations.

The huge benefit of the matrix game approach is that we could tailor the discussion to key issues and explore a range of options for representing various real-life security counter-measures. For example, the security threat level was assumed to constrain Red’s freedom of manoeuvre but that it could not be sustained for extended periods unless it was localised. Understandably, Red adjusted their strategy to minimise any increase in threat level (and quickly developed a healthy level of paranoia about Blue knowledge and capabilities) so this simple mechanism helped to heighten the realism of the game.

The narrative looked at each phase of Red’s plan, from smuggling in weapons and personnel, establishing a safe-house in the target city to setting the conditions for the final attack. The adjudicator used the arguments and counter-arguments to review each phase and to indicate to the Blue players their perception of the level of threat, and the probable targets they needed to watch or secure. The game process encouraged players to lay the foundations for future success by planning for contingencies and the discussions on how these options might develop enabled us to identify a number of useful indicators and warnings for real-life security scenarios.

Overall Insights

- The matrix game approach is a powerful tool for eliciting subject matter expert insight on complex questions. The process is fast flowing and highly flexible; enabling the group to highlight emerging issues and exchange views on both scenario specific and general challenges, and to evaluate potential mitigations.

- “Matrix Game Style Resolution” can easily be inserted into conventional games. Anything that isn’t explicitly covered by clear rules and verified tables can be handled by a matrix game style discussion/argument.

- We recommend using between five and nine people (including subject matter experts). You need enough players for a wide-ranging discussion to emerge naturally as the narrative unfolds.

- A decent sized room with a large map is vital. In addition, the importance of providing food and drink should not be underestimated – too many breaks (or discomfort) can undermine immersion and break the flow of information exchange.

- The best way to learn how to adjudicate a game is to take part in a couple of matrix games and watch how an experienced adjudicator facilitates a narrative. The core challenges are subject matter awareness (expertise is useful but not essential) and the ability to maintain narrative momentum.

- Players quickly recognise that strong arguments help them achieve objectives and the astute ones also realise they can cunningly lay the foundations for future success.

- While more effort may be required to provide analytically rigorous quantitative data from a matrix game, it is an efficient and cost-effective process for generating qualitative output which can then be subjected to quantitative analysis. It can also be used to identify the key areas where the next phase of detailed analysis needs to be concentrated.

- The concepts being tested need to be more than a single technology. We found that the capabilities of a coherent system (including basic tactics, techniques, and procedures) were easier to articulate and evaluate.

- Each system needs a champion. The advantage of a champion is that they understand the system (often playing a key role in its development) and will thus be keen to explore its potential. We were extremely lucky with our concept champions as they were both enthused about their concepts and keen to debate their merits.

- The champion needs to be open-minded and happy to hear counter-arguments. While you want someone who is keen to develop and then defend their concept, you don’t want someone who will become defensive or angry.

- The Adversary (Red) team need to be highly experienced in the area you want to examine. The optimum is to have an established critical thinker (to play the adversary and to introduce plausible reasons for friction) and at least one subject matter expert (to ensure that the challenge of each vignette or mission is both appropriate and realistic).

- It is best to test your new concept against a current threat first. This ensures that Red fully understands the concept being tested and they are therefore better equipped to develop a plausible version (or counter) for the mission adversary. This approach also enables the concept champion to identify and correct fundamental issues (the kind that would naturally emerge as the concept develops) before the more challenging scenarios are explored.

- The process requires at least a day to review each vignette as most games will require at least six turns to establish a coherent narrative.

Matrix gaming is a powerful narrative-based analytical approach that we found both useful and engaging/immersive. Tactical challenges are often difficult to quantify in look-up tables and we found that these complex questions can be more fully explored through Matrix game-based discussion and argument in the context of a tailored scenario.

Neat to see the Kit in action. I’ve enjoyed my copy.

I’ve just put up a new web page of free hobby Matrix Games. They are the games I’ve run at Conventions the last two years.

https://sites.google.com/view/free-engle-matrix-games/home