Picture credit: King’s Wargaming Network.

This year’s Connections UK professional wargaming conference was held at King’s College London on 3-5 September. Participants from almost two dozen countries countries took part, making it one of the most international Connections conferences ever. Of the 285 who registered for the event, about 13% were women. A very large proportion were also younger and first-time participants, underscoring the success of the conference in growing the wargaming community and reaching out to a new generation of serious gamers.

UPDATE: audio and/or slides from all of the conference presentations are now available from the Connections UK website.

Day 1

The first day of Connections UK was divided into several streams.

Some participants took part in a full day introduction to wargaming course, taught by Major Tom Mouat (Defence Academy of the UK) together with Jerry Elsmore. According to Tom:

The “Introduction to Wargaming” course was attended by over 60 people. The course included presentations on “Why Wargame”, “Types of Wargame”, Wargaming Effects, Hybrid Warfare and Influence”, “Wargame Design, Dice and Adjudication” and “Wargaming Pitfalls and Dangers”. I also demonstrated a simple Kriegsspiel based on counter IED operation in Afghanistan, a modified commercial-off-the-shelf game Air Strike (based on IAF Leader by Dan Verssen Games) and a matrix game Kazdyy Gorod about an Eastern European city on the border with Russia, faced with internal dissent and “little green men”. After the session, I also gave an additional lecture on “Game Components and Map Making”.

Jim Wallman (Stone Paper Scissors) ran a full day megagame, Super Soldiers & Killer Robots 2035, which looked at the impact of technological innovation on warfare.

Finally, there was an array of types of shorter games that participants could play.

- Map and counter: Ukraine Crisis– Rik Stolk and Graeme Goldsworthy

- Map and counter: Afghanistan Provincial Reconstruction Team(PRT) Game – Roger Mason

- Map and counter plus negotiation: 2nd Punic War– Phil Sabin

- Map & counter computer-assisted wargame: RCAT Full-Spectrum Adjudication– Graham Longley-Brown, Jeremy Smith, Dstl, NSC and Slitherine

- Card-driven game: Cyber resilience game – LTC Thorsten Kodalle

- ‘Euro-style’ board game: AFTERSHOCK Humanitarian Crisis Game–Rex Brynen

- Board game: Integrity: Conflict Sensitivity and Corruption– Paul Howarth

- Matrix game: Hybrid campaign game– Anja van der Hulst

I ran two games of AFTERSHOCK, both of which saw the players do a quite good job of bringing much-needed humanitarian assistance to the earthquake-affected people of Carana.

Your scribe, about to start a game of AFTERSHOCK.

Impressively, Day 1 also saw a visit by the UK Secretary of State for Defence, Ben Wallace, who toured some of the games in progress.

Day 2

The first plenary, chaired by Dr. Aggie Hirst (KCL), addressed the psychology of wargaming.

Captain Philip Matlary (Norwegian Army) addressed the psychology of teaching tactics. He stressed that understanding tactics is a cognitive skill, involving judgment, speed and guile. Since students construct their own understanding, teachers must attend to what students are thinking. Teaching tactics is intended to transform tactics from cognitive, “system 2” analytical thinking to more intuitive “system 1” thinking. However, system 1 thinking—although faster— is also prone to bias and systematic errors, such as confirmation bias and cognitive ease. He emphasized the importance of developing guile. Left somewhat open was how good wargaming was at developing these skills (compared to other methods), how we know this, and what best practices might be. Dr. Neil Verrall, a psychologist with Dstl, addressed the psychology of wargaming. He usefully broke down the internal dynamics of the game (intrapersonal/player characteristics interpersonal/the psychology of individual interaction, and group dynamics) and external dynamics (the context of the game). He stressed the importance of addressing these (confounding) variables, adopting an experimental mindset in game design and execution. He concluded with some food for thought, including cross-cultural gaming, organizational cultures, the role of information, understanding and deception, and responses to future threats. He also underscored the importance of interdisciplinary (or transdisciplinary) approaches to improve wargame design. Finally, Dr. Yuna Wong (RAND) addressed the importance of bringing psychological insights into wargaming. She argued that a lot of political science/international relations training was at the wrong level of analysis to address small group wargame dynamics. She also identified several barriers to bringing psychology more fully into wargaming. These included disciplinary barriers; the excessive quantitative focus of (US) social science and a corresponding atrophying of qualitative analytical skills (“some social scientists could no longer pass the Turing Test”); the lack of senior wargame mentors in psychology; and the failure to recognize psychology and an important area of subject matter expertise in games (as opposed to domain, geographic area or technological knowledge).

Aggie suggested a series of question to start off the discussion period, and then threw it open to the audience to raise additional points. I raised two: first, the issue of how we can psychologically manipulate wargame participants to behave in certain desired ways, and second the psychology of wargame promotion. Regarding the later, I warned of our l own vulnerability to confirmation bias—I think, as a community, we are sometimes prone to oversell our favoured approaches.

Following the coffee break, we broke into four simultaneous “deep dive” sessions:

- Quantitative vs qualitative gaming (Phil Sabin)

- Answering “so what” questions (Jim Wallman)

- Successful playtesting (Graham Longley-Brown and James Bennett)

- Data capture and analysis (Colin Marston)

I attended the latter, although I’ll admit that my arrival in the session was delayed by extended discussions with colleagues over coffee that ran late.

The first keynote of the conference was delivered by Dr. Lynette Nusbacher (Nusbacher Associates). Entitled “There’s No Pro like an Old Pro: Professionalism and Wargaming,” she addressed how games can more effectively shape policy processes. She discussed the value of gaming as a forming of inoculation against strategic surprise and shock. When senior leaders encounter cognitive dissonance and ideas for which they are not prepared for they may stop thinking. Challenge may be unwelcome. At its base, she stressed, simulation and gaming should introduce disruption. In the UK, she suggested, government does not really develop strategy to implement policy, but tends to reverse the direction. Strategy is just presumed to exist. There is typically no structured process to marshal ways and means to deliver ends. The US benefits from a more robust think-tank community (partly as a home for former or aspiring political appointees) that are more receptive to critical analysis.

Keynote address by Lynette Nusbacher.

The wargaming and simulation community needs to continue to sell gaming to think tanks and universities. Wargaming is still too dependent on creative and ambitious individuals adopting the technique. Gaming needs to be a fundamental part of procurement. Gaming needs to be sold not only on the internal merits of the game, but as a general antidote to some of the endemic pathologies of UK policymaking.

After lunch, there was yet more wargaming available for participants to sample.

- Anti-Submarine Warfare: a game for understanding the basics – Ed Oates

- Crisis in Zefra: An analytical matrix game – US Naval Postgraduate School

- The Camberley Kriegsspiel– Ivor Gardiner

- Signal– Sandia Labs and Berkeley

- Sweeping Satellites–Mike Sheehan and Mark Flanagan

- FITNA: The global war in the Middle East– Pierre Razoux

- Dogfight– Phil Sabin

- Decisions and Disruptions cyber game – Dr Ben Shreeve

- Rosenstrasse – Graham Longley-Brown

- Fire and Movement– Mark Flanagan

- Next War: Poland – Callum Nicholson

- Confrontation Analysis: Wargaming the US/China trade war – Dstl

- We Are Coming, Nineveh! –Rex Brynen

- A Reckoning of Vultures (Matrix Game Construction Kit) –Rex Brynen

- The Al Asqa Intifada – Stella Guesnet

- Beggars in Red: The Battle of Waterloo – James Bridgman

- Cyber card game– Dstl

- Combat Mission tactical computer wargame – Dstl

- STRIKE! – Dstl

- Strategic Wargame Verden Crisis – Dstl

- Canvas Aces –Phil Sabin

- Kursk to Kamenets: The battle for the Ukraine 1943-1944 – James Halstead

Our game of We Are Coming, Nineveh! saw Iraqi security forces liberate west Mosul after six months of heavy fighting—but at the cost of massive collateral damage. Because of this it was judged to be a Daesh victory.

We Are Coming, Nineveh!

Coup plotting underway in Matrixia—the “Reckoning of Vultures” scenario from the Matrix Game Construction Kit.

Day 3

Day 3 started off with the usual housekeeping announcements, then a short presentation on the future of Connections UK. Registrations have increased year to year, although it might soon be running up against space limitations at KCL. Moving ahead there will be some institutionalization of the organizational structures have made it all possible.

The first plenary session was on gaming hybrid warfare, chaired by John Curry (History of Wargaming Project).

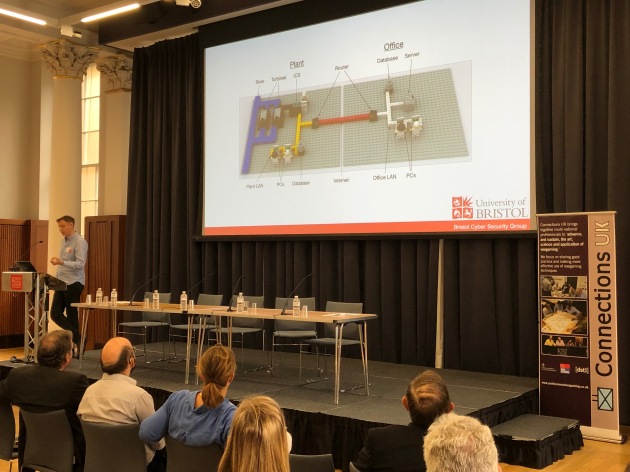

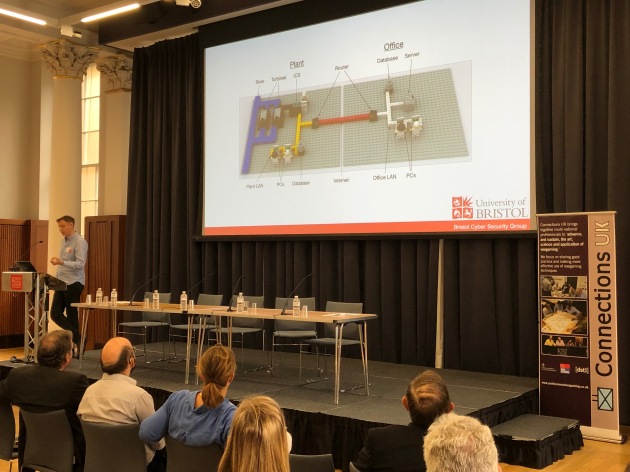

Dr. Ben Shreeve (University of Bristol) delivered an outstanding presentation on “decisions and disruptions.” He first introduced a simple card game (with awesome Lego illustrations) that he uses to educate about cyber vulnerabilities and mitigation. He then discussed a study of how different groups played the game, finding that security experts actually played slightly worse than IT managers or computer scientists. Security experts tended to underinvest in basic cyber defences (such as antivirus and basic security training) and instead emphasized more sophisticated capabilities. They also analyzed the kinds of arguments used to support decisions. A full paper on their findings (by Sylvain Frey, Awais Rashid, Pauline Anthonysamy, Maria Pinto-Albuquerque, and Syed Asad Naqvi) can be found here. Next, Dr. Anja van der Hulst(TNO) examined wargaming the hybrid threat. In it she reviewed the various approaches, such as matrix games, scripted connect-the-dots games, and others. Usefully she highlighted the strengths and weaknesses of each approach. Finally, Dr. Roger Mason looked at wargaming hybrid warfare cyber operations. After a review of the role of cyber in hybrid and conventional operations, he introduced The Battle of Voru, a wargame exploring the employment of cyber in a fictional Russian attack on Estonia.

Ben Shreeve on gaming cyber security.

John led off discussion by noting that one needs to match wargaming tools to the sort of hybrid warfare issue or question that one is examining. One of the audience expressed some concern about “hybrid” warfare in that all warfare is hybrid, and that combining the terms might obscure that some “hybrid” activities might actually seek to avoid kinetic warfare. (This is rather a hobbyhorse of mine, so I was happy to hear someone raise it.) There was also discussion of the role of non-state actors. I asked about the risk that sponsors want games with exaggerated (cutting-edge, trendy hybrid and cyber threats)—especially there is some evidence from Ukraine and Syria that tactical and strategic cyberattacks have actually had fairly limited effects.

The conference again broke into “deep dive” groups, before and/or after lunch:

- Wargaming the Future

- Space Games

- Technology to Support Wargaming

- On Wargaming

- Data Capture and Aanlysis

Once again, I found myself in side discussions and saw less of these than I wished. However, Stephen Aguilar-Millan was kind enough to provide a summary of the first of these sessions, which he cochaired and led.

The session orignated in some thinking about wargaming the future that was undertaken for Connections US. The whole point of thought is to lead to some purposeful action, so we decided to hold a session at Connections UK that would start to act out this process. We decided to examine ‘The European Battlespace 2050’ as the topic of invetstigation and we aimed at unearthing the critical strategic uncertainties that a wargame would be concerned with. The session attracted about 60 participants, with a wide variety of national, organisational, and occupational responsibilities. They were divided into ten groups of six participants and tasked with defining the Blue Team in the European Battlespace in 2050. A set of strategic assumptions were given to the participants, along with a map and a set of crayons. Their output was an annotated strategic map of Europe in 2050, which was presented to the group in the second half of the session. The plan is for the session curators to take the maps after the conference, synthesise the information contained on the maps, and to look for the key strategic uncertainties facing Europe in 2050. This output has the potential to then feed into the next stage of the process – to build a set of scenarios from which the game dynamics can be created.

In the afternoon, the next plenary session, chair by Colin Marston, addressed the selection and use of commercial off the shelf and modified off the shelf (COTS/MOTS) Games. Jim Wallman (and an absent Jeremy Smith from Cranfield University) offered an air COTS review, in which they examined 17 COTS tactical air combat wargames. Each was assessed against 32 criteria. They also asked, more generally, if the games addressed future technology insight, whether the game was useful for training or development, whether it was useful for capability, how easily it was modifiable, and the game’s learning curve (how quick and easy it was to learn to play).

Paul Beaves then discussed a land COTS review, which examined existing commercial manual urban warfare games for the purpose of supporting future Dstl wargame development. They focused on games that addressed battlegroup-level operations. They evaluated the extent to which the games addressed a variety of Ministry of Defence requirements—for example, did it address line-of-sight, varying terrain types, and command control. Among those assessed was We Are Coming, Nineveh! Not surprisingly, each of the games had strengths and weaknesses, none fully covered all UK requirements, and many had useful approaches and features.

![]()

![]()

LtCol Ranald Shepherd (British Army) addressed COTS wargames and professional development, largely focussing on A Distant Plain. When running games in Afghanistan, participants found themespecially useful in highlighting the divergent interests of the key parties. He suggested that more could be done to use COTS games to support professional development.

![]()

![]()

Finally, Wilf Owen raised someconcerns about professional wargames. He stressed at the outset that wargames were extremely valuable tools when well executed by skilled and knowledgeable personnel. However, not all wargames are good. COTS games too often use hexes, too rarely have single player/level of command issues. Digital COTS games run into blackboxing problems. Wargames are too often too different from actual military procedures, and real-world military experience should count for more than skill with the game system. Wilf noted that there was little systematic evidence of the value-added of wargaming. He suggested combat resolution models are less important than people think, and that games need to focus more on the consequences of decisions. He stressed using real maps of real terrain using real planning processes and procedures. It was an excellent presentation, although on some issues he may have underestimated the extent to which his critical views are actually quite widely held in the community.

The second keynote address of the conference was provided by Maj Gen Mitch Mitchell (Development, Concepts and Doctrine Centre), who spoke about the importance of “thinking differently.” Given a changing international system, how could horizon scanning and gaming help us be better prepared? Wargaming needs to become both routine (something regularly done) and experimental (in that it examines new threats and responses).

The last plenary presentation was offered by me, on gaming peace and stabilization operations. The slides for my presentation can be found here (pdf).

This was Phil Sabin’s last Connections UK as a faculty member at KCL, since he is now embarking on a well-deserved retirement. During the conference several of us spoke to his contributions to teaching and research on wargames and military history, to wargame design, and to building a professional community. Indeed, his conflict simulation course in the Department of War Studies was the orignal inspiration for my own course at McGill university, where we use his book Simulating War as the course text.

All in all it was an excellent conference. Special thanks are due to everyone who made it happen—the organizers, the student volunteers (without whom there would have been chaos), and the Department of War Studies at King’s College London.

Thanks for the report!

I wish I’d been there. Next year for sure.

Crisis in Zefra – guess they borrowed the Zefra setting from the narrative written for the Canadian Army by science fiction writer Karl Schroeder.

Whose presentation is the pictured in the “Urban Areas and Cities” photo?

Were those four urban operations games pictured on the slide the only four reviewed by Paul Beaves?